Introduction

The term “malocclusion” encompasses all deviations of the teeth and jaws from normal alignment, including a number of distinct conditions, like discrepancies between tooth and jaw size (crowding and spacing), malrelationships of the dental arches (sagittal, transverse, and vertical) and malpositioning of individual teeth.[1] Angle’s classification of malocclusions is universally accepted because of its simplicity as a method of description and communication between dental professionals.

Based on the relationship of the mandibular first molars to the maxillary first molars, this system characterizes the Class II malocclusions as having a distal relationship of the mandibular teeth relative to the maxillary teeth of more than one-half the width of the cusp. Two distinct types of Class II malocclusion exist, differing in the inclination of the maxillary central incisors. Class II Division 1 malocclusions exhibit labially inclined maxillary incisors, an increased overjet with a vertical incisor overlap varying from a deep overbite to an openbite and the Class II Division 2 malocclusion showing excessive lingual inclination of the maxillary central incisors accompanied by a deep overbite and minimal overjet. An Angles Class III malocclusion means that the mandibular first molar is anteriorly placed in relation to the maxillary first molar. It is a symptomatic or phenotypic description that uses the first molars and canines as criteria, and it has nothing to do with the maxillary and mandibular skeletal bases.

Class II molar relationship may occur unilaterally, depicted or classified as a class II “subdivision” of the affected side[2] or a bilaterally Class II on both the sides which is a frequently occurring type of malocclusion out of these two.[3]

Methodology

The current study was carried out in the Orthodontic department of Dr. Harvansh Singh Judge Institute of Dental Sciences, Panjab University, Chandigarh. Data for the study were collected from the patient’s records who reported at the department for orthodontic treatment during the period from April 2008 to December 2011. A total of 768 patients were evaluated for the study. All the patients were examined for screening to include subjects with full complement of permanent teeth up to second molars. The patients with the history of previous orthodontic treatment, extractions of permanent teeth other than 3rd molars, mixed dentition, congenital malformations like Cleft lip or/and palate, systemic diseases and patients with Class I and pseudo Class III were excluded from the study.

In addition to the clinical examination, study casts, photographs, lateral cephalograms and orthopantomograms were also evaluated to verify the diagnosis. Patients were labelled for any of four categories of malocclusion on the basis of following features:

Class II, division 1 group: Convex soft tissue profile; excessive overjet (more than three mm); protrusive maxillary incisors; Angle Class II molar relationship in centric occlusion.

Class II, division 2 group: Decreased anterior facial height; excessive overbite (more than three mm); retroclination of two or more maxillary incisors; Angle Class II molar relationship in centric occlusion.

Class II subdivision group:

Unilateral molar class II relationship with class I molar relation on opposite side in centric occlusion.

Class III group: concave soft tissur profile; Angle’s Class III molars and canines, retroclined mandibular incisors, and the presence of an edge-to-edge or an anterior crossbite occlusion. Angle Class III molar relationship in centric occlusion.

Results

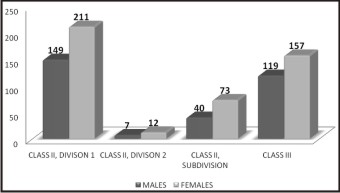

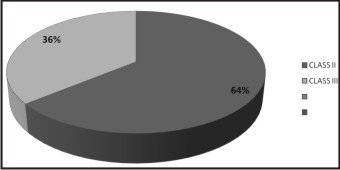

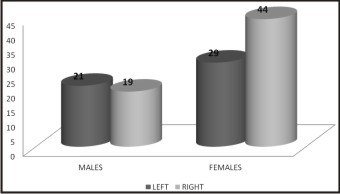

Screening of the total sample of 768 patients consisted of 315 males and 453 females. Age group of patient was from the range of 11.5 years to 32 years. Among 768 patients, class II malocclusion patients were 492 and 276 patients were of Class III malocclusion. (Figure 1), (Figure 2). Out of 492 patients of Class II malocclusion; 360 patients (males165 and females 195) were of Class II division 1; 113 patients (males 40 and females 73) of Class II subdivision; and 19(males 7 and females 12) patients were of Class II division 2 malocclusion. Out of 113 patients of Class II subdivision left subgroup were 50(males 21 and females 29) and right subgroup were 63(males 19 and females 44) Of 276 patients of Class III malocclusion, sex distribution determined was of 131 males and 145 females. (Figure 3), (Figure 4).

| Figure 1: Gender Distribution Of Malocclusion (N=768)

|

| Figure 2: Frequency Of Class II & Class Iii Malocclusion

|

| Figure 3: Prevalance Of Malocclusion In Chandigarh Sample (N=768)

|

| Figure 4: Distribution Of Left And Right Subgroup Of Class Ii Subdivision (N=113)

|

Discussion

Several studies have evaluated the prevalence of malocclusion in different populations. The results of studies may show great variability due to the differences in classification of occlusal relationships, the developmental period of the study sample, examiner differences, and differences in sample sizes. Instead of differentiating normal and abnormal in a population, determining frequencies of different types of malocclusions in an orthodontically referred population may also give valuable information[4]. This study was conducted in patients referred to the Department of Orthodontics, Dr Harvansh Singh Judge Institute of Dental Sciences, Panjab University, Chandigarh, for orthodontic treatment. This study was carried out as no local study with this magnitude of patients sample size had been carried out in the past. Analysis of a large sample of more mature permanent dentition is mandatory in order to obtain a clear and valid picture of the distribution of occlusal patterns in any given population.

In general, girls report and seek orthodontic treatment more frequently than boys.[5],[6],[7] This factor was reflected in our sample as well.

The methods of recording occlusal traits can be broadly divided into qualitative and quantitative measurements. These methods are useful in describing the occlusal traits for categorizing various types of dental malocclusions for quick and easy documentation as well as providing a common channel of communication among dental professionals. Literature shows that these methods have been used extensively in malocclusion prevalent studies[8]. Although the Angle classification was developed more than a century ago, it still remains the most commonly used classification of malocclusion and its universal acceptance by the dental professionals is evidence of its practicality.[9]

Angle’s classification is reliable and valuable in assessing the anteroposterior dental arch relationship. The conflicting evidence seen in results is likely to be related to the type of samples being studied, which may be either clinical samples or random samples drawn from a population[10]. In most of the surveyed populations Class II malocclusion has been found to be more prevalent than the Class III.[11] This finding goes with our results as well. Roughly one-third of the North American population and half of all orthodontic patients present with some sort of Class II malocclusion.[12]

Several genetic and environmental interacting factors are related to the etiology of these malocclusions. Soft diet, mouth breathing, tongue thrusting, sleeping posture, sucking, and other habits as well as specific factors (skeletal growth disturbances, muscle dysfunction, disturbances in embryologic and dental development) interact with heredity in the development of major types of malocclusion. These factors are difficult to separate, in terms of gene-environment interactions. Intraoral environmental change may be a decisive factor, but this change may also reveal previously masked genetic effects.

In United States prevalence of Class II malocclusions in population have been quoted from 55.1 per cent (age 8–11) to 67.7 per cent (age 12–17). In comparison to US population being dependent on industrially processed foods, the inhabitants of isolated traditional communities utilize more traditional and home-produced foods providing consistent loading during mastication.[1]

An ultra-orthodox Jewish community in Jerusalem has shown prevalence of 32% for class II/1, 2.3% for class II/2 and 8.5% for class II subdivisions in its children. However, low prevalence of normocclusion (7.4%) can be attributed to genetic background, environmental influences and the definition used for normal occlusion[13]. Sample of Caucasian’s orthodontic patients has shown even larger proportion of class II malocclusion around 70%, far above that of the population sample.[14]

A large Indian sample of children from rural areas have exhibited a prevalence of 13.5% for class II malocclusions[15]. The Class II/2 malocclusion is relatively rare, with a frequency between 1.5 and 5% of all malocclusions. It is more common in females. Findings were quite consistent with our results. Class II/2 malocclusion has not only a specific pathognomonic dental appearance, but it also has several skeletal, sagittal, and especially vertical attributes that differentiate it from both Class I and Class II/1 malocclusions.[16] Unilateral Class II cases were classified as subdivision cases by Angle. He reported that a Class II molar relationship developed because of the distal eruption of the mandibular first molars in relation to normally positioned maxillary first molars.[17] This category of class II malocclusion has consistently shown a prevalence of more than class II/2, but less than that of class II/1[14], [18]. The same trend also expressed itself in current study.

The prevalence of Class III malocclusion varies among different ethnic groups. The prevalence of this type of malocclusion in the Caucasion population is approximately 3-5%.[19]

Conclusion

The prevalence of class II malocclusion was more than class III in sample from orthodontic patients visiting orthodontic department of institute in Chandigarh is quite high, representing approximately one third of our orthodontic population. Class II/div1 is prominently more prevalent than the other categories of class II malocclusion. In class II subdivisions, right side is affected most of the times than the left side.Also the orthodontic awareness was also also found to be more among females than males as the proportion of females visiting orthodontic department is more than males. The obvious reason for this is esthetics, which are of more concern for females.

References

1. Lauc T. Orofacial analysis on the Adriatic islands: an epidemiological study of malocclusions on Hvar Island. Eur J Orthod 2003; 25: 273–78

2. Bishara SE. Class II malocclusions: diagnostic and clinical considerations with and without treatment. Semin Orthod 2006; 12:11-24.

3. Filho OGD, Ferrari Jr FM, Ozawa TO. Dental Arch Dimensions in Class II division 1 Malocclusions with Mandibular Deficiency. Angle Orthod 2008; 78: 466-74.

4. Sayin M, Turkkahraman H. Malocclusion and crowding in an orthodontically referred Turkish population. Angle Orthod 2004; 74:635–39.

5. Afzal A, Ahmed I, Vohra F. Frequency of malocclusion in a sample taken from Karachi population. Ann Abbasi Shaheed Hosp Karachi Med Dent Coll 2004; 9: 588-89.

6. Kerosuo H, Kerosuo E, Niemi M, Simola H. The need for treatment and satisfaction with dental appearance among young Finnish adults with and without a history of orthodontic treatment. Am J Orthod 2000; 61:330–40.

7. Kerosuo H, Abdulkarim E, Kerosuo E. Subjective need and orthodontic treatment experience in a Middle East country providing free orthodontic services: a questionnaire survey. Angle Orthod 2002; 72: 565-70.

8. Soha J, Sandhamb A, Chan YH. Occlusal status in asian male adults:prevalence and ethnic variation. Angle Orthod 2005;75: 814–20.

9. Bernabe E Sheihamb A, deOliveira CM. Condition-specific impacts on quality of life attributed to malocclusion by adolescents with normal occlusion and class I, II and III malocclusion. Angle Orthod 2008; 78: 977-82.

10. Zhoua L,Moka C, Haggb U, McGrath C, Bendeusd M, Wua J.Anteroposterior dental arch and jaw-base relationships in a population sample. Angle Orthod 2008; 78: 1023-9.

11. Danaie SM, Asadi Z, Salehi P.Distribution of malocclusion types in 7-9- year-old Iranian children. East Mediterr Health J 2006; 12: 236-40.

12. McNamara Jr JA,Johnston Jr LE.Introduction:Perspectives on Class II Treatment. Semin Orthod 1998; 4: 1-2.

13. Ben-bassat Y, Harari D, Brin I. Occlusal traits in a group of school children in an Isolated society in Jerusalem. Br J Orthod 1997; 24: 229–35

14. Proffit WE, Fields HW, Sarver DM.Contemporary Orthodontics. 4th ed. St Louis, Mo: Mosby Year Book; 2007:194.

15. Guaba K, Ashima G, Tewari A, Utreja. A.Prevalence of malocclusion and abnormal oral habits in North Indian rural children. J Indian Soc Pedod Prev dent 1998; 16: 26-30.

16. Brezniak N, Arad A, Heller M, Dinbar A, Dinte A, Wasserstein A. Pathognomonic Cephalometric characteristics of Angle Class II Division 2 Malocclusion. Angle Orthod 2002; 72: 251–57.

17. Kurt G, Uysal T, Sisman Y, Ramoglu SI. Mandibular Asymmetry in Class II Subdivision Malocclusion. Angle Orthod 2008; 78: 32-37.

18. Yang WS . The study on the orthodontic patients who visited department of orthodontics, Seoul National University Hospital.Taehan Chikkwa Uisa Hyophoe Chi 1990; 28: 811-21.

19. Massler M, Fr~inkel JM: Prevalence of malocclusion in children aged 14-18 years. Am J Orthodont 1951; 37:751-68.

|